Chapter 1: Introduction

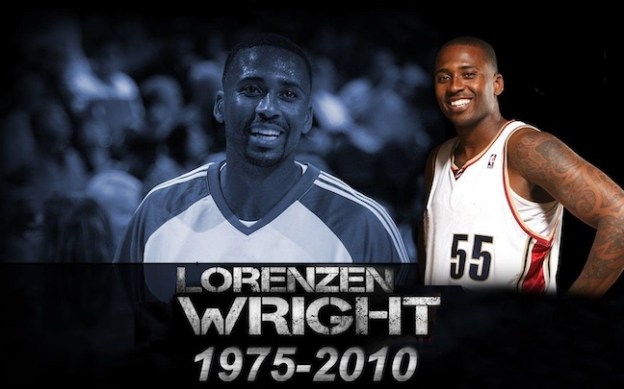

The murder of former professional basketball star Lorenzen Wright remains one of the most disturbing true crime stories in sports history. Once a beloved basketball star in Memphis and across the National Basketball Association (NBA), Wright’s life ended in a brutal killing that shocked the sports world and launched a years-long investigation filled with mystery, betrayal, and unexpected suspects. This FreeSportsMag exclusive investigative story explores what happened to Lorenzen Wright, how police solved the case, and why the tragedy continues to draw attention in true crime, sports crime, and unsolved mystery discussions online.

Chapter 2: A Rising NBA Star

Before his name appeared in crime headlines and murder investigations, Lorenzen Wright was known as a talented professional basketball player.

Wright starred at the University of Memphis and became a local legend of sorts before entering the National Basketball Association. In the 1996 NBA Draft, he was officially selected seventh overall by the Los Angeles Clippers. During a 13-year NBA career, Wright also played for the Memphis Grizzlies, Atlanta Hawks, Sacramento Kings, and Cleveland Cavaliers.

At 6’11”, Wright was known for his defense, rebounding, and physical style of play. But more importantly, he was deeply connected to Memphis, where he grew up, played for the Grizzlies, and later returned to live after his NBA career. His reputation in the community was that of a generous and approachable figure who regularly gave back to local charities.

That reputation made what happened in 2010 even more shocking.

VISIT THE FREESPORTSMAGZINE.COM MEMORABILIA & COLLECTIBLE STORE ON EBAY

Chapter 3: The Disappearance

On July 18, 2010, Lorenzen Wright left his home in Memphis. It was the last time anyone saw him alive. His family reported him missing several days later, triggering a missing persons investigation by the Memphis Police Department. Concern quickly spread throughout Memphis and the NBA community as media outlets began covering the mysterious disappearance of Lorenzen Wright.

Then a strange piece of evidence surfaced.

Nine days after Wright vanished, emergency dispatchers received a 911 call from Wright’s phone. The recording captured gunshots and Wright apparently shouting in distress before the line went dead. Investigators immediately suspected foul play, but the call offered little information about the location or identity of the attacker. For weeks, the case remained a haunting mystery.

Chapter 4: A Grim Discovery

On July 28, 2010, authorities discovered Lorenzen Wright’s body in a wooded field near Callis Cutoff Road outside Memphis. He had been shot multiple times.

The discovery confirmed what many feared: this was not just a missing person case but a high-profile murder investigation involving a former NBA star. Investigators began examining Wright’s finances, personal relationships, and recent activities. Early speculation in the true crime community ranged from robbery to gambling debts to organized crime, but no clear suspect emerged for years.

The case gradually went cold.

Chapter 5: The Investigation Reopens

For nearly seven years, the Lorenzen Wright murder case remained one of Memphis’s most notorious unsolved crimes.

Then, in 2017, investigators received a breakthrough.

Authorities recovered the murder weapon—a handgun found in a Mississippi lake. Ballistics confirmed it was the gun used in Wright’s killing. The discovery reignited the investigation and led detectives to revisit earlier suspects.

The case began to point in a shocking direction.

Chapter 6: The Role of Ex-Wife

Investigators ultimately determined that Wright’s ex-wife, Sherra Wright, had played a central role in the crime. According to prosecutors, Sherra Wright conspired with a man named Billy Ray Turner to murder the former NBA player.

The motive, as old as time, allegedly involved financial problems she was having and a multimillion-dollar life insurance policy she was set to inherit.

In 2019, Sherra Wright pleaded guilty to facilitation of murder and received a 30-year prison sentence. Billy Ray Turner was later convicted of first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder, bringing long-awaited closure to a case that had haunted Memphis for nearly a decade.

Chapter 7: The Chilling 911 Call

One of the most unsettling aspects of the Lorenzen Wright case remains the 911 recording. The call, made moments before his death, captured Wright shouting and gunshots firing in the background. Investigators believe he was attempting to call for help while being attacked. The recording circulated widely online and became a focal point for true crime documentaries, podcasts, and investigative journalism, adding to the case’s notoriety.

Chapter 8: Legacy and Impact

The murder of Lorenzen Wright left a lasting mark on Memphis and the NBA community. His family created the Lorenzen Wright Foundation, which provides support for single mothers and families in need. The organization seeks to preserve Wright’s legacy as a compassionate community figure rather than allowing his story to be defined solely by tragedy.

Today, the case remains one of the most widely discussed true crime sports cases, often appearing in documentaries, podcasts, and investigative reports examining celebrity murders and sports-related crimes.

Chapter 9: Conclusion

What began as a missing NBA player case evolved into a complex murder investigation that took nearly a decade to solve. While the convictions of those responsible brought legal closure, the story of Lorenzen Wright remains a powerful and tragic chapter in both NBA history and American true crime investigations. It serves as a haunting example of how violence can intersect with fame, money, and personal relationships and raises lingering questions about warning signs, financial pressures, and the hidden struggles athletes may face after their playing careers end.